Fertility of immigrant women and daughters of immigrants

More children, but fewer per woman

Published:

This article was first published in Norwegian, in Statistics Norway’s journal Samfunnsspeilet: Tønnessen, Marianne (2013): Fruktbarhet hos innvandrerkvinner og døtre av innvandrere. Flere barn, men færre per kvinne. Samfunnsspeilet 5/2013. Statistisk sentralbyrå.

An increasing number of children born in Norway - and a quarter of all children born in 2012 – have a mother who is an immigrant. Nevertheless, fertility among most groups of immigrant women in Norway has decreased over time. The decline has been strongest among women from Asia, Africa and Latin America. Daughters of immigrants appear to have a significantly lower fertility rate than their mothers.

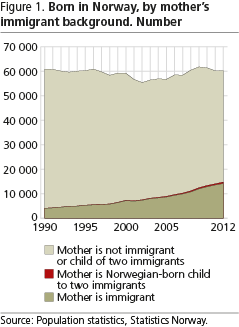

The share of babies born to immigrant women in Norway is steadily increasing. Last year, 23 per cent of newborns – nearly one in four – were born to a mother who was an immigrant. Fifteen years ago, the corresponding figure was fewer than one in ten. A large part of the general increase in the number of newborns in Norway over the past decade is due to the rise in the number of immigrant women having babies, as shown in Figure 1.

More female immigrants in Norway…

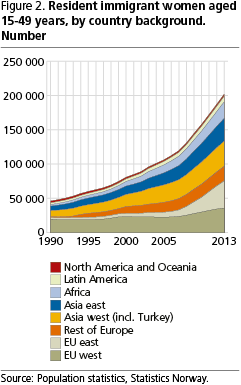

A growing number of births in Norway are to immigrant mothers. However, it is not the case that each immigrant women is having more children than previously. The reason for the increase is the rise in the number of immigrant women of childbearing age (15-49 years) living in Norway. In just 20 years, the figure has quadrupled, from just below 50 000 in 1990 to over 200 000 in 2013 (see Figure 2).

All of the large country groups in this study (see textbox on country groups) have seen an increase in the number of immigrant women of childbearing age, and growth has been greatest among women from the new EU countries. Since 2004, when the EU was extended eastward, the number of women aged 15-49 years from the eastern EU countries living in Norway has increased six fold.

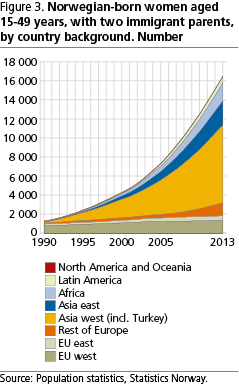

Many immigrants have children and live for a long period of time in Norway, and their children eventually grow up and have children of their own. The number of women of childbearing age who are Norwegian-born to two immigrant parents has risen sharply since 1990. This group is dominated by young women who have parents from western Asia (see Figure 3). This is related to the fact that many of the Pakistani immigrants have lived in Norway for a long time, so their children are now adults.

Although this group has shown a clear growth - since 1990 there has been over twelve times as many daughters of two immigrants of childbearing age – it is still a relatively small group. In 2013, the group totalled 16 500, which corresponds to 8 per cent of the women who are immigrants themselves.

…but fewer children per woman

In other words, it is the number of immigrant women of childbearing age that is the reason behind immigrant women in Norway giving birth to so many children. The fertility rate among immigrant women, i.e. the average number of children per woman (see explanation in textbox), has not increased. On the contrary, the fertility rate among immigrant women has generally fallen since 1990.

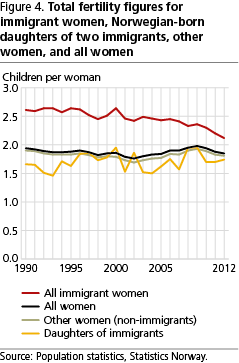

The total fertility rate (TFR) has changed in recent decades, for immigrant women, Norwegian-born daughters of two immigrants and other women in Norway, as shown in Figure 4. The average fertility rate for all immigrant women remained mostly above 2.5 before the end of the millennium, but has since fallen. In 2012, the immigrant women had, on average, 2.1 children per woman.

The line for “all women” is slightly higher than the line for “other women (non-immigrants)” because the immigrant women pull the general fertility rate in Norway slightly up. However, the immigrants’ contribution to the general fertility rate is relatively small - the two lines run approximately parallel, and the distance is a maximum of 0.07 children per woman. Thus, the immigrant women have pulled the TFR in Norway up somewhat, but not more than 0.07 in any year.

For the immigrant daughters (yellow line in Figure 4), the TFR fluctuates considerably from year to year. This is because there are still relatively few women in this group, which means that random variations can have a major impact. We must not, therefore, be too quick to draw conclusions from these figures. However, it would appear that fertility among the immigrant daughters is significantly lower than that of their mothers, and possibly also slightly lower than that of other women in Norway.

Why the decline?

Why has fertility among immigrant women fallen? There may be several reasons. One explanation may be that the composition of immigrants has changed.

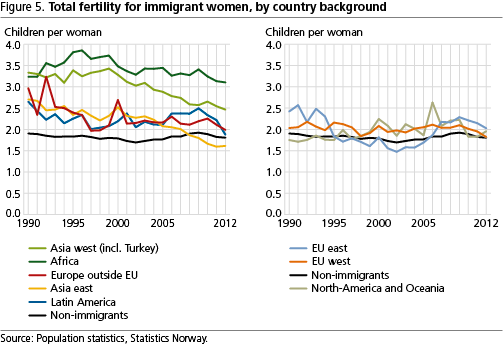

As shown in Figure 1, there has been a significant increase in the number of women of childbearing age from East Europe over the last decade. The fertility rate in many East European countries has been low for a long time. Figure 5 shows that there are great disparities in fertility according to which part of the world the women are from. Figure 5 (left area) shows the trend among immigrant women in the country groups that had a significantly higher fertility rate than other women in Norway in the early 1990s. This applies to women from Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe outside the EU. The fertility rate in all these groups has shown a decline over the past 20 years, particularly for women from both east and west Asia.

The fertility rate of women from the EU, North America and Oceania does not differ much from that of non-immigrants (see right area of Figure 5). Neither do we find the same tendency for a falling fertility rate among these women as among immigrant women from other regions. The fertility rate of women from the eastern EU countries has actually increased since 2000, and particularly since the expansion of the EU in 2004. This may be because a large number of the women who have immigrated to Norway from the new EU member states over the past decade have followed (or arrived with) a labour immigrant and started a family in Norway.

It is therefore not the case that a larger share of immigrants from eastern EU countries is the main reason for the overall decline in fertility among immigrant women. A more important explanation is found among the women who have had the greatest decline in fertility: women from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Longer period of residence – fewer children

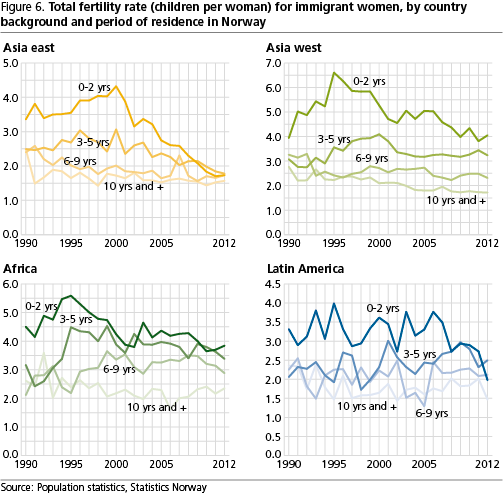

Why has the fertility rate fallen among immigrant women from Asia, Africa and Latin America? One way to examine this is to compare women from the same area but with different periods of residence in Norway.

This highlights two main trends, as shown in Figure 6: First, the fertility rate is higher the less time the women have lived in Norway. This is the case whether the women are from Asia, Africa or Latin America. The women with the shortest period of residence (0-2 years) have, in many cases, more than double the fertility rate of those with the longest period of residence (over 10 years). This may partly be because many women come to Norway for the purpose of starting a family. Moreover, it is conceivable that refugees postponed having children for a period of time before coming to Norway. It may also be a sign that many change their mind about how many children they want to have as they get to know and are influenced by Norwegian society.

Second, we see that among those with the shortest period of residence the fertility rate is now considerably lower than it was a few decades ago. This also applies to the women from Asia, Africa and Latin America. Thus, the newly arrived women today have markedly fewer children than the newly arrived had previously. Given that they are new arrivals, this development can hardly be explained by their integration with Norwegian society. Asia east now has almost no disparities between periods of residence.

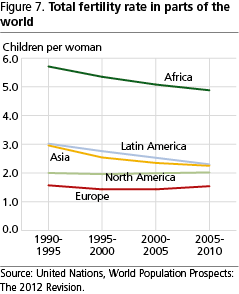

Also lower in country of origin

One explanation for the change among women with a short period of residence can be found by examining the fertility rate in the areas where the immigrant women travel from. Statistics from the United Nations show that the number of children has declined considerably in many parts of the world in recent decades (see Figure 7). From the period 1990-1995 to the period 2005-2010, the fertility rate fell by more than 0.8 children per woman in Africa and 0.7 children per woman in Asia and Latin America. In some important countries of origin (i.e. important in a Norwegian immigration context), the TFR sank even more in this period; Pakistan went from 5.7 to 3.7 - a decline of two children per woman. The women who immigrated to Norway in 2012 from these areas thus came from countries that were characterised by a lower fertility rate than previously.

More reasons for fall in fertility rate

The fertility rate among immigrant women has thus fallen by about 0.5 per woman since 1990, and there may be several reasons for this. The share of immigrant women from eastern EU countries has increased, and these have traditionally had a lower fertility rate than women from countries outside the EU. However, in recent years, the fertility rate among East European immigrant women has been high, so the main reason for the overall decline does not lie here.

A more important reason is found among the immigrant women from Asia, Africa and Latin America. The fertility rate in these groups has fallen in recent decades, which may partially be explained by the fall in fertility the longer these women have lived in Norway. However, since immigration has been high in recent years, there is still a large share of immigrants with a short period of residence in Norway. Among these we find a central explanation as to why the immigrant fertility rate in Norway has decreased:

Today›s newly arrived immigrant women from Asia, Africa and Latin America have a much lower fertility rate than the newly arrived immigrant women from these parts of the world 10-20 years ago. This may be related to changes in the countries they have travelled from. In most countries of the world, women are now having fewer children than a few decades ago.

Contact

-

Statistics Norway's Information Centre