Statistical analysis, 2017

Statelessness – a major global problem

Statelessness: many worldwide, few in Norway

Published:

This article was first published in Norwegian, in Statistics Norway’s journal Samfunnsspeilet: Brunborg, Helge (2016): Statsløshet – et stort globalt problem. Statsløse: mange i verden, få i Norge. Samfunnsspeilet 4/2016. Statistisk sentralbyrå.

Around 2 400 stateless persons live in Norway, most of whom are refugees. Worldwide, the figure is approximately 10 million, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The biggest problem for stateless persons with a residence permit in Norway is the lack of passport, while those in many other countries have considerably greater problems, often facing discrimination and almost total exclusion from society.

- Series archive

- Statistical analysis, 2017

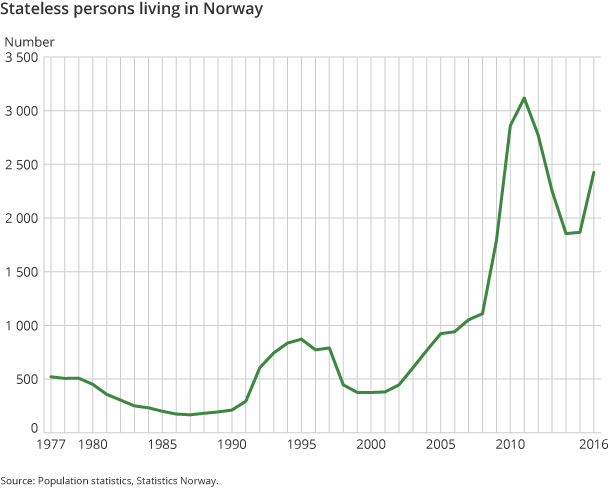

There are relatively few stateless persons in Norway: 2 425 at the start of 2016. However, the number has fluctuated considerably from year to year, mostly due to immigration and naturalisation. The peak was reached in 2011 at just over 3 000, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

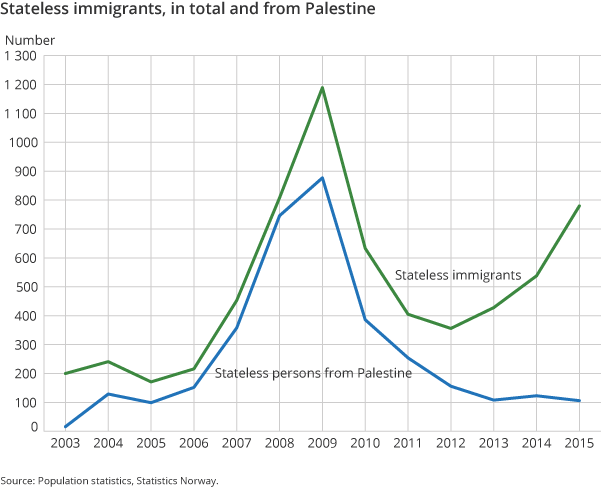

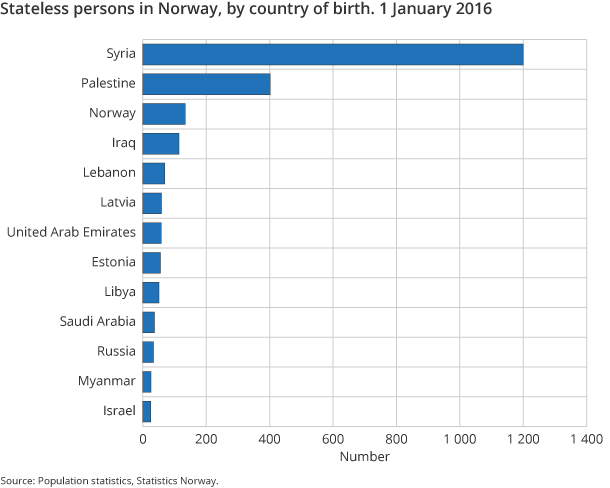

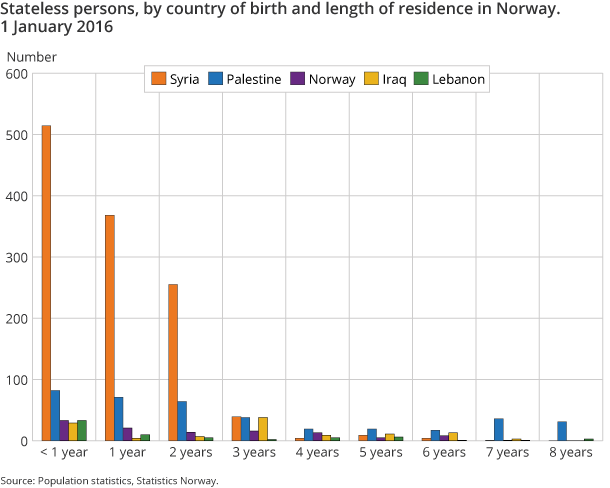

In the years 2003–2015, a total of 6 400 stateless persons immigrated to Norway. Of these, 3 500 were Palestinians, with most arriving in 2009 (877 persons), see Figure 2. Today the largest groups of stateless persons in Norway were born in Syria (1 200), Palestine (402) and Norway (134), see Figure 3. In recent years, there has been an increasing number of stateless persons from Syria, as well as a significant increase in those born in Palestine, Norway, Iraq and Lebanon, which reflects the rising numbers in recent years, see Figure 4.

Some of those born in Syria and Iraq may also have a Palestinian background, but we have no information on that. Almost all stateless persons in Norway are refugees or family members of refugees. Only 4 per cent of stateless persons immigrated for other reasons, such as work and education. The majority of stateless persons outside Europe are not refugees.

Most become Norwegian citizens

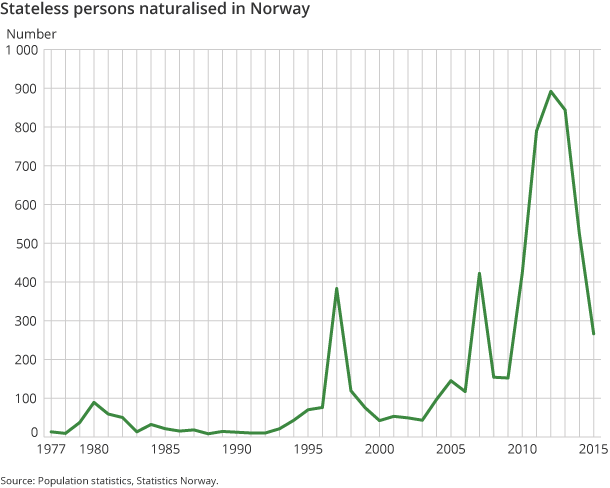

The main reason for the decline in the number of stateless persons in Norway in recent years is that many have become Norwegian citizens, as shown in Figure 5. In the years 2003 to 2015, 4 900 stateless persons – most of whom immigrated during the same period – were naturalised in Norway, see Table 1. Stateless persons over the age of 18 can apply for Norwegian citizenship if they “have resided in the realm for the last three years and have a residence permit of at least one year’s duration” (Norwegian Nationality Act 2015). Children of naturalised citizens can also apply, but they must have lived in the country for the preceding two years. This is considerably shorter than for most other non-Nordic immigrants, who must have lived here for seven years. For more statistics on Norwegian citizenship, see Pettersen (2015).

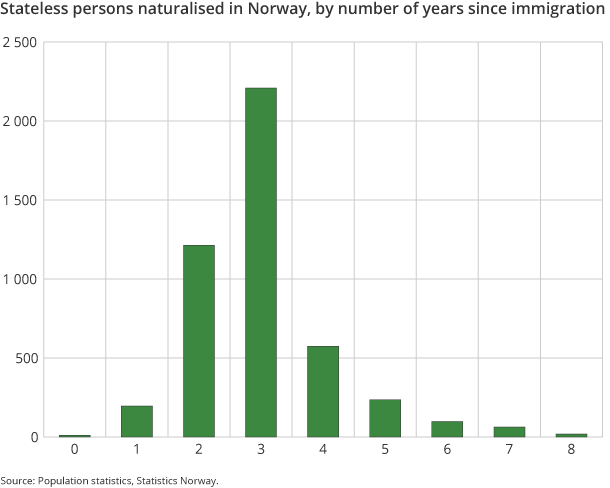

Most Norwegian naturalisations occur three years after immigration, see Figure 6. After four years, 90 per cent of the stateless immigrants have become Norwegian citizens, and only 3 per cent have lived here for ten years or longer without naturalising. Eighty-three per cent of children who are born to stateless parents in Norway have been naturalised four years after birth, and only 2 per cent have lived here for ten years or longer without naturalising.

Not many stateless persons emigrate from Norway, with an average of just 30 per year since 2003 (Table 1).

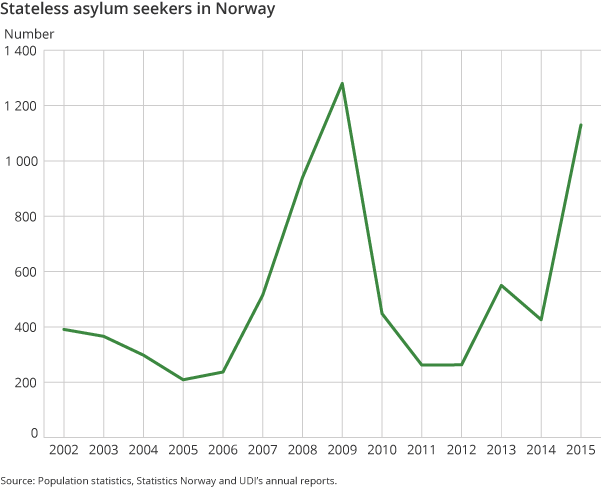

Many stateless persons have applied for asylum in Norway, as shown in Figure 7 and Table 1, but they still make up a modest share of asylum seekers in Norway, with almost 6 per cent during the period 2007–2014 (UDI 2016). Statelessness does not automatically qualify a person for a residence permit in Norway, but in 2015, 88 per cent of all asylum applications for residence permits from stateless persons were successful.

The number of stateless persons among those living in Norway without a residence permit, such as those without documentation, is unknown.

Although the number of stateless persons in Norway today is modest, it may grow significantly, particularly if the number of refugees from Syria increases again.

Why are children born without citizenship in Norway?

There is a wide held belief that when a child is born in Norway it automatically becomes a Norwegian citizen, however this is not the case. In the period 1986–2015, 997 children were born in Norway without citizenship. These children had stateless parents when they were born. A child becomes a Norwegian citizen at birth if the father or mother is a Norwegian citizen (Norwegian Nationality Act 2015), regardless of whether they are resident in Norway or not. The principle that a child’s citizenship is determined by the parents’ nationality is known as jus sanguinis, and is applied in most countries in the world, but not in the USA, where all newborns are entitled to US citizenship (jus solis). UNHCR recommends that all children born in Norway should be granted Norwegian citizenship, as in Denmark, where the authorities grant Danish citizenship to children whose home is in Denmark. This is consistent with Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states that all children from birth have the right to acquire a nationality (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1989).

The government recently (21 October 2016) adopted new instructions on the conditions for Norwegian citizenship for stateless persons born in Norway. The instructions specify that they must have been permanently resident in Norway for three consecutive years preceding the application for citizenship. If the parents have a permanent residence permit, children can acquire citizenship within one year after birth (Ministry of Justice and Public Security 2016).

Deficient legislation?

In many countries, stateless persons have problems acquiring birth certificates for their children and identity cards for themselves. Without such documents, it can be difficult to secure basic rights to health and education services, gain access to the labour market, travel, own land and other property, open a bank account, obtain a driving licence, inherit assets and marry. Stateless persons may also be arrested or expelled, and are often subjected to discrimination and harassment. They are often among the poorest in the population, as in Myanmar and Kenya. It is important that the human rights of stateless persons are protected, even though they are not recognised by any country.

Stateless persons in Norway have few problems compared to those in many other countries. A report by UNHCR (2015) notes, however, that Norwegian legislation has several gaps and weaknesses. Stateless immigrants are not necessarily granted residence in Norway.

- The two UN Conventions relating to the Status of Stateless Persons of 1954 and 1961 and the European Convention on Nationality of 1997 are not explicitly incorporated into Norwegian law.

- There is no definition of statelessness in Norwegian legislation.

- Norway has no special procedures for determining statelessness.

- There is no recognised stateless status providing for the rights of stateless persons, except that a shorter period of residence is required for obtaining Norwegian citizenship than for other non-Nordic citizens.

UNHCR (2015) points out that these shortcomings in the Norwegian legislation are in breach of international conventions to which Norway has acceded, and recommends that the UN convention is incorporated into Norwegian law. The Standing Committee on Local Government and Public Administration of the Parliament has raised this issue and stated that it “expects the government to ensure that Norwegian legislation in this area is in line with our international obligations” (Standing Committee on Local Government and Public Administration 2015–2016).

References

Council of Europe. (1997). European Convention on Nationality, ETS No.166. Retrieved from http://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/166

UNHCR. (1954). Convention related to the status of stateless persons. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/protection/statelessness/3bbb25729/convention-relating-status-stateless-persons.html

UNHCR. (1961). Convention on the reduction of statelessness. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/protection/statelessness/3bbb286d8/convention-reduction-statelessness.html

Meld. St. 30 (2015–2016). (2016). Fra mottak til arbeidsliv – en effektiv integreringspolitikk. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-30-20152016/id2499847/sec1

Ministry of Justice and Public Security. (2016). Instruks om tolkning av statsborgerloven – gjeldende rett for statsløse søkere som er født i Norge. (Rundskriv G-08/2016). Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/instruks-om-tolkning-av-statsborgerloven----gjel- dende-rett-for-statslose-sokere-som-er-fodt-i-norge/id2518182/?utm_source=www.regjeringen.no&utm_medium=epost&utm_campaign=Innvandring-28.10.2016

Innst. 399 S. (2015–2016). Innstilling fra kommunal- og forvaltningskomiteen om Fra mottak til arbeidsliv – en effektiv integreringspolitikk og Representantforslag fra stortingsrepresentantene Karin Andersen og Audun Lysbakken om å sikre integrering. Retrieved from https://www.stortinget.no/globa- lassets/pdf/innstillinger/stortinget/2015-2016/inns-201516-399.pdf

Pettersen, S. V. (2015, 07.01.). Stadig lavere andel som tar norsk statsborgerskap. Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/stadig-lavere-andel-som-tar-norsk-statsborgerskap

Statsborgerloven. (2015). Lov om norsk statsborgerskap. Retrieved from https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2005-06-10-51/KAPITTEL_3#KAPITTEL_3

Søbye, E. (2015). Tap av borgerrett. I K. S. Bull (Red.), Borgerrolle og borgerrett (s. 102-114). Oslo: Dreyer Akademisk publisering.

UDI. (2015). Annual reports. Retrieved from https://www.udi.no/statistikk-og-analyse/arsrapporter/ UN

UNHCR. (2015). Mapping Statelessness in Norway. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/docid/5653140d4.html

UNHCR. (2014). Global Action Plan to End Statelessness 2014- 2024. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/protection/statelessness/54621bf49/global-action-plan-end-statelessness-2014-2024.html?query=global

UNHCR. (2016a). Statelessness Around the World. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/statelessness-around-the-world.html

UNHCR. (2016b). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2015. Retrieved from https://s3.amazonaws.com/unhcrsharedmedia/2016/2016-06-20-global-trends/2016-06-14-Global-Trends-2015.pdf

UNHCR. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx

St. prp. nr. 75 (1956). Om innhenting av Stortingets samtykke til å ratifisere konvensjonen om stats- løses stilling av 28. september 1954: Tilråding fra Utenriksdepartementet 23. mars 1956 godkjent ved Kronprinsregentens resolusjon samme dag. Retrieved from https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og- publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1956&paid=2&wid=a&psid=DIVL1111&pgid=a_0751

Valgloven. (2002). Lov om valg til Stortinget, fylkesting og kommunestyrer. Retrieved from https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2002-06-28-57/KAPITTEL_2#KAPITTEL_2

Contact

-

Statistics Norway's Information Centre