Statistical analysis, 2017

Refugees and their educational background

Education from back home

Published:

This article was first published in Norwegian, in Statistics Norway’s journal Samfunnsspeilet: Bjugstad, Hanne Kure og Anne Marie Rustad Holseter (2016): Flyktninger og utdanningsbakgrunn. Med utdanning i bagasjen. Samfunnsspeilet 4/2016. Statistisk sentralbyrå.

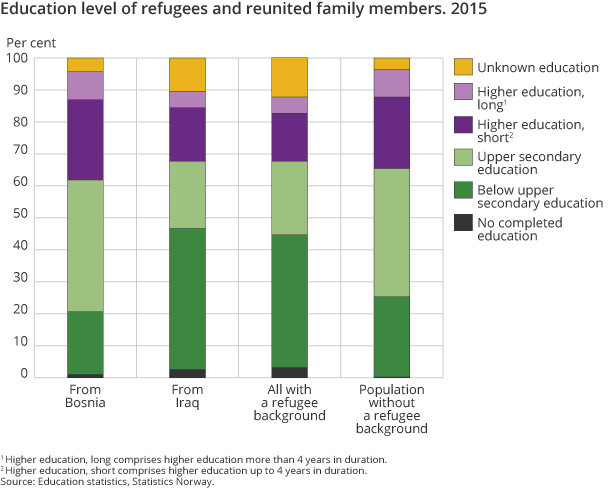

Gaining a foothold in the labour market and settling in Norway can be largely dependent on the education a refugee has from their homeland. Education levels differ considerably depending on country background: 44 per cent of Iraqi refugees have primary/lower secondary schooling as their highest completed education, which is above average for refugees in general, while the corresponding figure for Bosnians is 20 per cent.

- Series archive

- Statistical analysis, 2017

Population figures show that around 177 000 refugees and reunited family members aged over 16 were resident in Norway in October 2015. Forty-two per cent of these have primary/lower secondary schooling as their highest completed level of education, while 20 per cent, or one in five, have education at university/university college (short and long) level. The corresponding share with a university/university college education among the rest of the population is 32 per cent (see Figure 1).

Of the 177 000 refugees and reunited family members, around 31 000 are from Iraq and Bosnia and Herzegovina, when these two groups are taken as a whole. This issue of Samfunnsspeilet has a particular focus on these two groups – both have lived long enough in Norway for statistics to be produced on their development and both come from war-torn areas, just like the asylum seekers from Syria. The education that Bosnians and Iraqis attained prior to arriving in Norway has impacted on their integration into Norwegian society, and the same will be the case for future refugees.

Statistics Norway's living conditions survey from 2006 showed that Bosnian refugees have one of the highest education levels among refugees in Norway, along with those from Iran and Chile. When the living conditions survey was conducted, people with a background from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Sri Lanka had the highest income levels among refugees in Norway, while those from Iraq were among the refugee groups with the lowest incomes (Henriksen and Blom 2006).

Most refugees have a primary/lower secondary education

We have examined the education levels of the Iraqi and Bosnian refugees aged over 16 who arrived in Norway after 1990. Iraqi refugees have a level of education that is almost equal to the average for refugees in general (see Figure 1). Figure 1 shows the highest completed level of education in October 2015, regardless of length of residence in Norway. Below upper secondary is the highest level of education for 44 per cent of Iraqis in Norway, while the corresponding share among Bosnian refugees is 20 per cent. Meanwhile, 10 per cent of Iraqi refugees have an unknown level of education, which presents a challenge in the education statistics on refugees.

The share with an unknown education is 6 percentage points higher for the Iraqis than the Bosnians, which can partly be explained by disparities in immigration patterns and length of residence. According to Statistics Norway's immigration statistics, 90 per cent of the Iraqi refugees have lived in Norway for less than 20 years. They mostly arrived around 2000, but larger groups have also arrived over several periods during these years. In addition, Norway has more refugees from Iraq than from Bosnia and Herzegovina, and there have been few from the latter since 1995 (Statistics Norway 2016). Meanwhile, more recent analyses of asylum seeker figures suggest a considerable increase in residents from Iraq in the years ahead (Østby 2015).

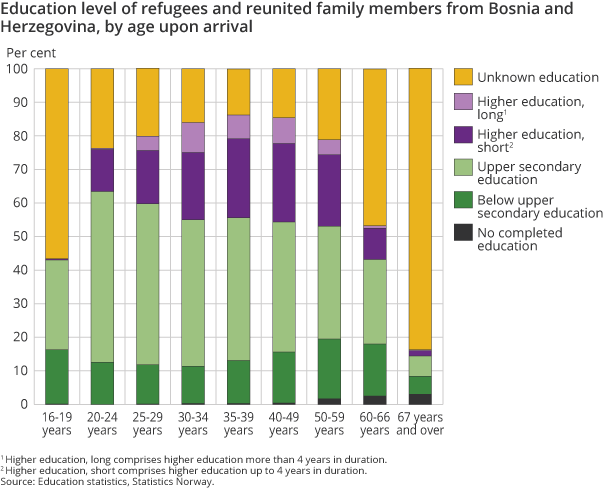

Among Bosnians, 67 per cent have lived in Norway for more than 20 years. Over the years, we have managed to collect more information about this group, and today only 4 per cent of the Bosnian refugees have an unknown level of education. This is clearly shown in Figure 5, which illustrates the registered education among Bosnian refugees upon arrival in Norway.

Bosnians are better educated than the average refugee

It is not only the share with an unknown level of education that distinguishes Bosnian refugees from Iraqi refugees and the average refugee. The largest share of Bosnian refugees in Norway have an upper secondary education (see Figure 1). With an 18 percentage point lead over other refugees in terms of upper secondary education, those from Bosnia and Herzegovina stand out from the average refugee.

Meanwhile, 34 per cent have a higher education (short and long). The share of Bosnian refugees with a long higher education is equal to the average for the population without a refugee background, at 9 per cent.

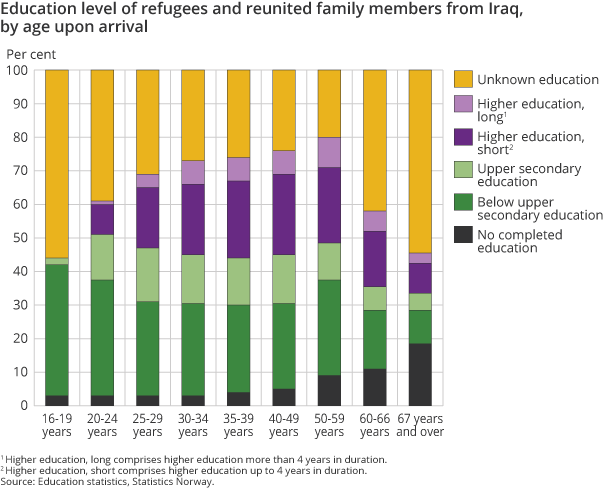

More than half of young Iraqis have an unknown education

There are major disparities between the level of education of Iraqi refugees on arrival and the education level of the population without a refugee background. The large share with an unknown education particularly skews the analysis of the group aged 16–19, where the share is 56 per cent. This may indicate that there have been many young refugees from Iraq in recent years and that a large share of these are not yet part of the Norwegian education system.

As in the general population, the group aged 30–60 has the highest education, with four in ten educated to upper secondary level or higher.

Iraqis have a long road to employment

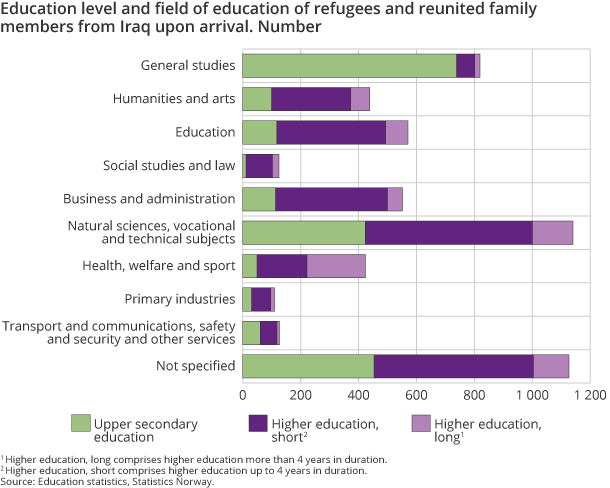

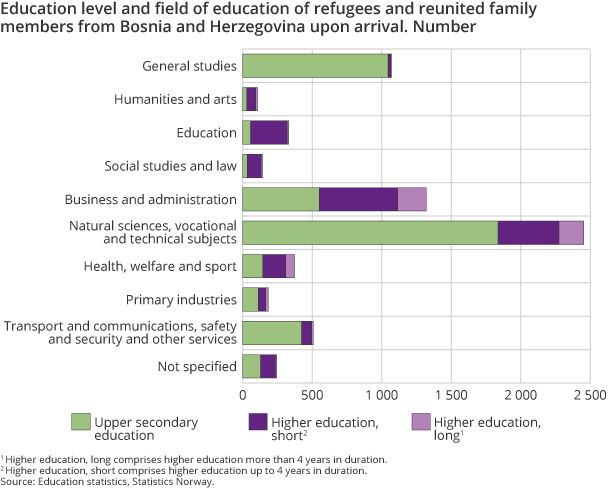

For refugees who were registered with an upper secondary education or higher, the largest group was Iraqi refugees with qualifications in natural sciences, vocational and technical subjects. Over 60 per cent of these have a university/university college education, 12 per cent of whom had studied at this level for more than four years. Other fields of education that are common are teacher education, business and administration, humanities and arts, and health, welfare and sport (see Figure 4).

Despite this well-educated share, refugees from Iraq, together with refugees from Somalia and Eritrea, have the lowest employment rate among refugees in Norway (Østby 2015). Employment generally increases in line with length of residence, but the high share with only a primary/lower secondary education means that this group also needs to spend a number of years studying in Norway before they can compete for jobs with the population without a refugee background and refugees from places like Bosnia and Herzegovina.

More Bosnians in employment

Around 40 per cent of Bosnians aged 20–50 had completed an upper secondary education prior to their arrival in Norway. Many in this age group also had a university/university college education, with almost a third of the 35–50 year-olds educated to this level (see Figure 5).

Most of the Bosnians whose education level was above primary/lower secondary had qualifications in natural sciences, vocational and technical subjects (see Figure 6). Among those with a higher education, many were graduates in business and administration, while a large share of those who had qualifications in teacher education, social sciences and law had also studied this at university or university college level.

In contrast to the Iraqi refugees, Bosnians are one of the refugee groups with a high employment rate in Norway, and the share has increased sharply since 1996, when many of the Bosnian refugees first arrived in Norway. Back then, 22 per cent of Bosnian refugees were in employment, while the current share is 60 per cent. As previously mentioned, employment increases in line with length of residence in Norway (Østby 2015).

Gender disparities – gap is smallest among Bosnians

Among Iraqi refugees, a higher share of men are educated at all levels, while a higher share of women have no education or an unknown education. This is also reflected in the employment rate, which is discussed in Helge Næsheim’s article on refugees in the labour market in this issue of Samfunnsspeilet. While about 50 per cent of men from Iraq are in employment, the share is well below 40 per cent for the women (Østby 2016).

Bosnian women also have a higher share with no education or an unknown education than the men, but at the same time, a higher share of women are university/college graduates. On the other hand, men have a 6 percentage point lead on women in terms of upper secondary education. The gender distribution among Bosnian refugees is thus almost equal, and they are also the only refugee group in Norway whose labour force participation has surpassed 60 per cent for both sexes (Østby 2015).

Improvements in registration of refugees’ education

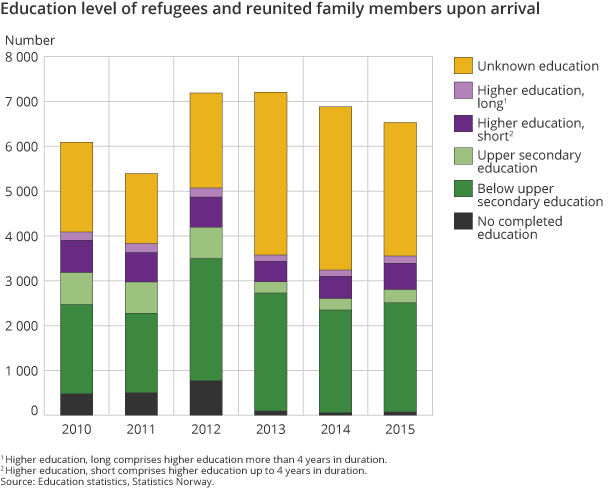

The reason for the lack of information on education levels is that there was previously no systematic registration of refugees’ education upon arrival in Norway, either for asylum seekers or quota refugees. In connection with the last census, Statistics Norway conducted three major surveys on immigrants’ education in order to obtain more knowledge on the subject. The surveys were carried out in 1991, 1999 and 2011–2012, and together with data from the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI) are the main source of information on refugees’ education upon arrival in Norway.

The registration of refugees’ education from their homeland has improved considerably in recent years. For asylum seekers, information on education is obtained during the settlement interviews conducted in asylum reception centres when an applicant has been granted residence and has been allocated a municipality of residence (Zachrisen 2016). Statistics Norway receives this information annually from the UDI. The process from when an applicant arrives in Norway until they are granted residence and Statistics Norway receives information on their education can, however, be quite lengthy.

More than half Norwegian-born with a Bosnian background are in education

We know that Norwegian-born children of immigrants participate in higher education to a greater extent than their parents (Henriksen 2007). The group Norwegian-born to immigrant parents is also more likely to pursue an upper secondary education than its peer groups (Dzamarija 2016).

Children born in Norway to Bosnian parents participate in higher education to a greater extent than is the case for the population as a whole. Almost 60 per cent of the girls and 42 per cent of the boys aged 19–24 whose parents are from Bosnia were in higher education in autumn 2015. The corresponding figures for the total population were over 42 per cent and 28 per cent respectively. The share in higher education among boys born in Norway to Iraqi parents was somewhat higher than for the population as a whole, at around 35 per cent in autumn 2015, while the corresponding share for girls was similar to the population as a whole.

References

Dzamarija, M. T. (Red.). (2016). Barn og unge voksne med innvandrerbakgrunn (Reports 2016/23). Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/273616?_ts=1562bfcd488

Statistics Norway. (2006, 06.02.). Levekår blant innvandrere, 2005-2006. Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/sosiale-forhold-og-kriminalitet/statistikker/innvlev

Henriksen, K. (2007). Fakta om 18 innvandrergrupper i Norge (Reports 2007/29). Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/a/publikasjoner/pdf/rapp_200729/rapp_200729.pdf

Statistics Norway. (2016). Innvandrere etter innvandringsgrunn, 1. januar 2016. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/statistikker/innvgrunn

Skills Norway. (2016). Om Vox. Retrieved from http://www.vox.no/om-vox/

Zachrisen, O. O. (2016). Hva vet vi om flyktningers utdanning?: Oversiktsartikkel, flyktninger og utdanning, 2016. Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/hva-vet-vi-om-flyktningers-utdanning

Østby, L. (2015). Flyktninger i Norge. Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/flyktninger-i-norge

Østby, L. (2016). Bedre integrert enn mor og far. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/sosiale-forhold- og-kriminalitet/artikler-og-publikasjoner/bedre- integrert-enn-mor-og-far

Contact

-

Statistics Norway's Information Centre