Statistical analysis, 2017

Introduction programme for newly arrived refugees

Women and men – Please, mind the gap!

Published:

This article was first published in Norwegian, in Statistics Norway’s journal Samfunnsspeilet: Enes, Anette Walstad (2016): Introduksjonsordningen for nyankomne flyktninger: Kvinner og menn – Please, mind the gap! Samfunnsspeilet 4/2016. Statistisk sentralbyrå.

Half of the women who participate in the Introduction programme for newly arrived refugees are in work or education one year after the programme. The political goal is 70 per cent. Men achieve this target, but women do not. Why is there such a gender gap? As they say on the London underground: Please, mind the gap!

- Series archive

- Statistical analysis, 2017

The Introduction programme for newly arrived refugees is the largest integration policy instrument that Norway has ever seen. Refugees who have been granted residence receive training that enables them to participate in the Norwegian labour market. The aim is to provide adequate basic training in Norwegian, teach them about Norwegian society and labour market initiatives, and to improve their chances of participating in working life and society, eventually leading to financial independence (Introduction Act 2003).

The target set by politicians is for at least 70 per cent of the participants to be in employment or education one year after the programme. Men achieve this target, but women do not: seven out of ten men are in employment or education one year after the programme, but this applies to only half of the women. Why is there such a gender gap?

What is the mark of success?

What is the mark of success of the Introduction programme based on its intention – that the former participants are in work or education in the years following the programme? Are there any typical features that stand out? In addition to men having a higher success rate than women, younger participants also do better than the older ones. Those who have an education from their home country fare better than those with a low level of education or no education. Married participants have a lower success rate than those who are not married.

We also observe that refugees from some countries generally do better than refugees from other countries: for example, participants from Eritrea, Ethiopia and Congo do well, while fewer of those from Somalia, Palestine and Iraq go into work or education (Enes & Wiggen 2016). Participants who have taken part in initiatives in the programme that are closely linked to the labour market or the education system also do comparatively better than the others (Blom & Enes 2015; Tronstad 2015).

What do women do after the Introduction programme?

A lot is known about women’s onward journey in society after the Introduction programme, but some groups of women are not represented in the statistics. This mainly applies to those who are taking a primary/lower secondary education or are at home with children.

We do not have information at an individual level for primary/lower secondary education, and this also applies to adults. It is therefore impossible to determine whether adults taking a primary/lower secondary education are in work or are receiving social assistance etc. Nor do we know the gender distribution in primary/lower secondary education for the former participants of the Introduction programme. If they are not included in any of the aforementioned groups, for instance in part-time work or claiming social assistance, we do not know their main activity. They will then be included in the group with ‘unknown status’. This also applies to women who stay at home with children.

Among the women, almost three in ten were working in 2014, and almost one in ten were both in work and education one year after the Introduction programme (see Table 1). This means that, in total, 36 per cent are either working full time or part time. More than half of the women in employment work in health and social services or cleaning (Enes & Wiggen 2016). Fourteen per cent are taking an education, either upper secondary or higher education. If we also include those who are both in work and education, the figure is 23 per cent.

One in ten are registered unemployed or on employment initiatives, and the share is the same for women and men. One in ten women receive social assistance. We have no information on what 14 per cent of the women do, while this applies to only 4 per cent of men. The figures are from 2014, but it is clear that they do not differ significantly from previous years.

Work – the litmus test for good integration

Norwegian women have the highest employment rate in the world. Many female immigrants come from countries that are at the other end of the scale. The norm and the goal is that everyone in Norway should work. Participation in working life is regarded as the litmus test for good integration (Meld. St. 30 (2015-2016)).

Employment is important for refugees both in order to learn Norwegian and about Norwegian society, as well as to build social networks through colleagues. Work is vital for self-esteem and for ensuring that everyday life is as similar to that of the majority population as possible. Perhaps most importantly, work is necessary to achieve financial independence.

Work is also important for the children of women with a refugee background. The mothers need to have paid work so that the children do not grow up in poverty. Higher incomes can mean fewer financial obstacles to attending day care facilities, or taking part in leisure activities, school trips, birthday parties and other social gatherings. It is also beneficial for children to see their mother taking part in Norwegian society in the same way as women in the majority population, and that they are not socially isolated or part of a group of other isolated mothers.

Why is there such a gender gap?

With a 20 percentage point lower share in work and education one year after the Introduction programme, women have a lower success rate than men (Enes & Wiggen 2016). The pattern is consistent every year. There can be many reasons for the gender disparity, some of which will be outlined here.

Women are older…

Women are generally older than men when they complete the Introduction programme. This is because a large share of the refugees are young men who come alone, while women often follow later together with their family (Blom & Enes 2015; Sandnes & Østby 2015). Women also spend longer on the Introduction programme than men, which is also part of the reason they are older when they finish. We have previously observed that the younger age groups fare better than the older ones. Since the women are older than the men, this can affect the results in the Introduction programme.

…and have a lower education

In a study of earlier participants who left the Introduction programme between 2007 and 2011, half of both the women and men had primary/lower secondary as their highest completed education, while one in ten had completed upper secondary school. Only one in ten women had a higher education, compared to two in ten men. Three in ten women were registered with ‘education not specified’ – twice as many as the men. We do not have data on these groups’ education.

In this group with an unknown education, we can assume that some people have little schooling, as they have very poor results in the Introduction programme (Blom & Enes 2015; Enes & Wiggen 2016). Only four out of ten with an unknown education were in work or education, compared to more than six out of ten where the education was known. A generally lower level of education may be part of the reason for the negative results for women.

Women’s country backgrounds differ from men`s

Women from Somalia and Russia are overrepresented among women who have been on the Introduction programme; they represent two groups that stand out with low shares in work and education after the programme. The men, on the other hand, have a larger share from, for example, Eritrea. Eritrean refugees do consistently well year after year. If the group of women has an overrepresentation of persons from countries that do poorly, and men have an overrepresentation of persons from countries that do well, this is likely to affect the mean results.

Who comes from which countries varies from year to year. It may be the case that we see more women from Eritrea in a few years if they are part of family reunification with men from the same country.

Mother and caregiver

After fleeing war and unrest, we see that women often have children shortly after they are settled. The birth rate in this country experienced an upswing after World War II. In a study of refugee women’s birth rates in Norway, Lappegård (2000) found that refugees had a particularly high birth rate during the first three years after their arrival. She also found that refugees who came to Norway to reunite with a spouse had children sooner after their arrival than those who came to the country with their family.

Many women in the Introduction programme have children during or immediately following the programme (Enes & Wiggen 2016; Lillegård & Seierstad 2013). Many refugee women also bring up their children on their own. In recent years, about one in ten participants have been a single parent (Enes 2014; Enes & Wiggen 2016). Consequently, many of the female participants are caring for young children – often several children. The refugee families are larger than families in the rest of the population. Couples with children, where at least one of the spouses participates in the Introduction programme, have an average of 4.5 family members, while families with children in the rest of the population consist of 4 people. The households of single parents on the Introduction programme consist of 3 people, while the corresponding figure for all single parents in Norway of a similar age is 2.6 (Enes & Wiggen 2016).

Many of the women have children with them upon arrival in Norway, and these children need to find their place in Norwegian society. They are in a country where everything is new; home, neighbourhood, friends, language, culture, kindergarten or school. Women are often the glue that holds the family together, ensuring that everyone is coping well and happy. They also tend to have more practical responsibilities for ensuring that all family members are properly fed and clothed etc. After a long journey from their homeland and separation from their father, the children may be more attached to their mother (Djuve, Kavli & Haglund 2011:57).

Cultural factors also play a role, with the lion’s share of responsibilities in the home and family, care and supervision of children resting with the women (Blom & Enes 2015; Djuve et al. 2011). Caring for young children and their integration into Norwegian society can often take the focus away from learning Norwegian and work practice. In order for women with young children to be able to participate in working life, they need a kindergarten place for their children, access to transport, and working hours that can be combined with family life.

In a study on refugee women on the Introduction programme (Djuve et al. 2011), FAFO researchers concluded that the main reasons why the women did not participate in work or education to the same degree as men were the large number of children they had and the high birth rate during the programme.

Long time – less intensive training?

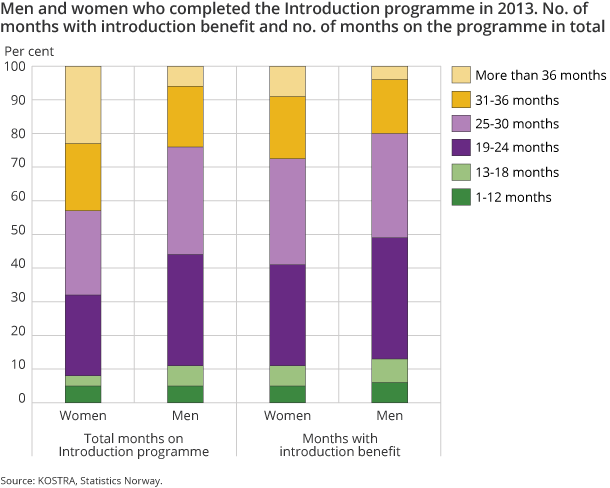

The Introduction programme should be adapted to individual qualification needs, in terms of both content and duration. Women spend longer on the programme than men on average (Enes & Wiggen 2016). Women who left the programme in 2013 spent an average of 30 months on the programme in total, compared to 25 for men. This calculation includes absence and various types of leave. We can assume that maternity leave is the main reason for this gender disparity.

The average time women spend on the programme is higher than the median, i.e. the middle value in the number of months in the programme (see box for more information). This suggests a rather extended programme for some women. The average is 30 months, while the median is 28.

In relation to the number of months that participants receive introduction benefit, which is an indication of active participation in the programme, the disparities are smaller; men received benefit for 24 months on average, while women received it for 26 months. Four in ten women received introduction benefit for up to two years, while over six in ten actively participated in the programme for more than two years. In comparison, half of the men spent two years or less on the Introduction programme. Among men, the distribution between the number of months on introduction benefit and the number of months from start to finish is relatively similar (see Figure 1).

Spending an extended period on the Introduction programme can in many cases result in a less intensive course of training, and the progress in learning Norwegian may therefore be slow (Djuve et al. 2011). This can particularly apply to the women, given that they spend longer than average on the Introduction programme.

Men arrive first, followed by women

The journey to Norway can be arduous and dangerous. The men often travel first, while the women and children follow later as part of family reunification (Sandnes & Østby 2015). Among the earlier female programme participants, there is an overrepresentation of family immigrants. However, there are more asylum seekers among the men (Blom & Enes 2015). We have already observed that refugees who arrive as asylum seekers generally fare well after the programme in terms of employment and education.

Most of the previous female programme participants are married. Most of the men are registered as not married. However, we cannot rule out a possible spouse in their homeland.

The largest age group among male programme participants in recent years has been 26–35. A number of these are likely to be married and are expected to apply for family reunification. The subsistence requirement for family reunification may be a motivating factor in finding employment as soon as possible. As mentioned above, being unmarried or single as an immigrant has a positive effect on participation in work or education (Blom & Enes 2015; Enes & Wiggen 2016; Tronstad 2015).

Do women get a raw deal?

Several studies have shown that the share in work or education in the years following the Introduction programme is higher for those who take part in initiatives in the programme that are closely linked to the labour market than for the other participants (Blom & Enes 2015; Enes & Wiggen 2016; Tronstad 2015).

We see that just as many women as men take part in Norwegian language training and social studies and have language practice. However, in relation to other initiatives that are more closely linked to the labour market, the share is higher for men. Fewer women undertake vocational practice, work experience or paid work as part of the programme (Blom & Enes 2015). If the Introduction programme is better adapted to men than women, this could have a bearing on women’s access to the Norwegian labour market.

Women’s participation in the programme can be affected by the time spent on maternity leave or caring for children. Djuve and her colleagues (2011) found that many programme advisors found it difficult to give women language or work practice when it was assumed they would have high absence levels. In many cases, the consequences were that the women were left with an Introduction programme that mainly consisted of Norwegian language training.

Can we approach this differently?

The gender gap in terms of participation in education and the labour market following the Introduction programme has several possible explanations.

Women are older than men at the end of the Introduction programme, and many are from countries that are associated with low participation in employment and education for women. Furthermore, women's educational levels are lower, and more women than men come to Norway as part of family reunification. These factors may help to explain the lower share of women in work and education.

If the Introduction programme is less well adapted for women, and many take part in a programme that almost entirely consists of Norwegian language training (Blom and Enes 2015; Djuve et al. 2011), this can be rectified by better adapting the programme for women.

Women need Norwegian language training, knowledge of Norwegian society and contact through employment, but having children is natural for them, whether they are from Baghdad or Bergen. One reason for refugee women’s poorer participation may just be the accumulation of demanding care tasks in this phase of life. They are often from countries where kindergarten is an unknown phenomenon or where places are limited. The threshold for participation in Norwegian society will therefore be higher for some women than for men. Many will need time to gain a foothold in the competitive Norwegian labour market with its strict qualification requirements.

Quantitative measurements mean that not all aspects of participants’ lives are observable. Social participation, which is also a goal of the Introduction programme, is one area that is not captured in the statistics, and neither is the value of children having a safe encounter with Norwegian society, and proper follow-up of their everyday life in kindergarten, school and leisure time. Due to care responsibilities, it can take several years for many of the women to acquire the language skills needed to go out to work.

References

Blom, S., & Enes, A. W. (2015). Introduksjonsordningen – en resultatstudie (Reports 2015/36). Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/introduksjons-ordningen-en-resultatstudie

Djuve, A.B., Kavli, H.C., & Hagelund, A. (2011). Kvinner i kvalifisering: Introduksjonsprogram for nyankomne flyktninger med liten utdanning og store omsorgsoppgaver (Fafo report 2011/02). Retrieved from http://fafo.no/index.php/nb/zoo-publikasjoner/fafo-rapporter/item/kvinner-i-kvalifisering

Enes, A.W. (2014). Tidligere deltakere i introduksjonsprogrammet 2007-2011: Arbeid, utdanning og inntekt (Reports 2014/15). Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/tidligere-deltakere-i-introduk- sjonsprogrammet-2007-2011

Enes, A. W., & Wiggen, K. S. (2016). Tidligere deltakere i introduksjonsordningen 2009-2013 (Reports 2016/24). Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/tidligere-deltakere-i-introduksjonsordningen-2009-2013

Introduction Act. (2003). Lov om introduksjonsordning og norskopplæring for nyankomne innvandrere. Retrieved from https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2003-07-04-80

Lappegård, T. (2000). Mellom to kulturer: Fruktbarhetsmønstre blant innvandrerkvinner i Norge (Reports 2000/25). Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/mellom-to-kulturer?fane=om

Lillegård, M., & Seierstad, A. (2013). Introduksjonsordningen i kommunene: En sammenligning av kommunenes resultater (Reports 2013/55). Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/introduksjonsordningen-i-kommunene

Meld. St. 30 (2015-2016) (2016): From reception center to the labour market – an effective integration policy. Retrieved from: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/meld.-st.-30-20152016/id2499847/

Sandnes, T., & Østby, L. (2015). Familieinnvandring og ekteskapsmønster 1990-2013 (Reports 2015/23). Retrieved from http://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/familieinnvandring-og-ekteskapsmonster-1990-2013

Skutlaberg, S., Drangsland, K.A.K., & Høgestøl, A. (2014). Evaluering av introduksjonsprogrammene i storbyene (Ideas2evidence-rapport 09:2014). Retrieved from http://ideas2evidence.com/sites/default/files/Evaluering%20av%20introduksjons-programmene%20i%20storbyene.pdf

Tronstad, K. R. (2015). Introduksjonsprogram for flyktninger i norske kommuner: Hva betyr organiseringen for overgangen til arbeid og utdanning? (NIBR report 2015:2). Retrieved from http://www.hioa.no/Om-HiOA/Senter-for-velferds-og-arbeidslivsforskning/NIBR/Publikasjoner/Publikasjoner-norsk/Introduksjonsprogram-for-flyktninger-i-norske-kommuner

Contact

-

Statistics Norway's Information Centre